Front Blog

See all ›Customer service

What your customers wish you knew: Insights from the state of service expectations

Today’s customers are in control, demanding faster, more efficient service with a balance of AI and human touch. Our latest research reveals insights into customer loyalty with the tools you need t...

Read more →Customer service

11 ways B2B teams can collect customer feedback at scale

Learn how to collect customer feedback beyond surveys, with proven methods and best practices to improve customer experience and loyalty.

Read more →Customer service

Anticipate customer needs with proactive customer support

Learn what proactive customer service is to anticipate customer needs and why it drives retention, satisfaction, and a stronger customer experience.

Read more →Workflows

Customer lifetime value: What it is and how to calculate it

Learn the formula for customer lifetime value (CLV), how it works, and how to grow long-term revenue by improving retention and loyalty.

Read more →Customer service

How to write customer satisfaction surveys that your team can act on

Discover six customer satisfaction survey questions every CX team should use and get tips for calculating CSAT and improving the customer experience.

Read more →Customer service

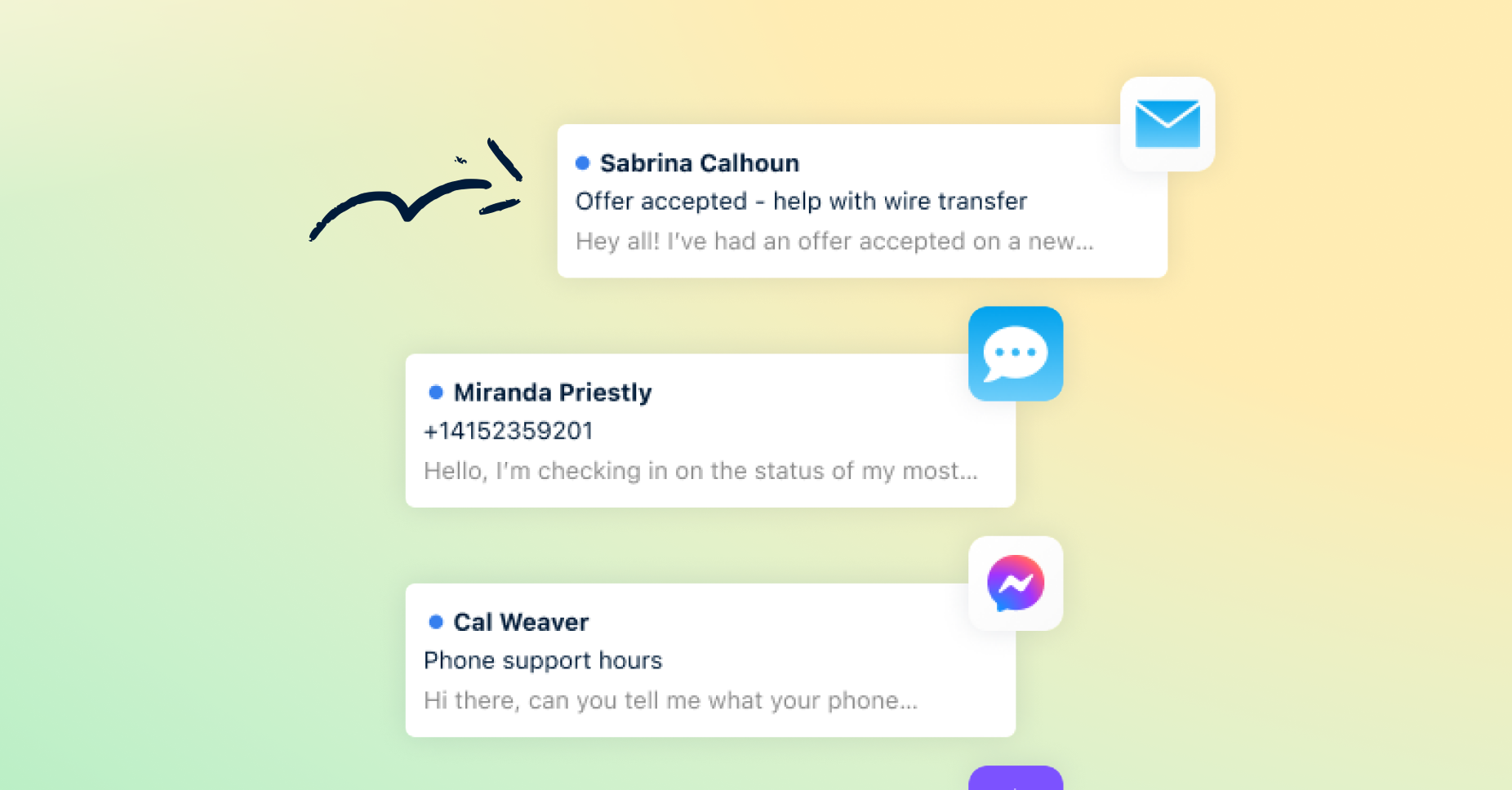

Live chat: What it is, how it works, and how to do it right

Learn what live chat is, how it works behind the scenes, and how teams use it to deliver fast, personal support across channels at scale.

Read more →Workflows

How to improve customer satisfaction: 6 strategies for B2B teams

Learn how to improve customer satisfaction with six proven strategies that help teams respond faster, personalize support, and build long-term loyalty.

Read more →News

While Retail Rang Up Sales, Manufacturing Teams Quietly Became AI Power Users

New data reveals where operational complexity, not transaction volume, drives AI adoption

Read more →Customer service

12 best AI customer service software tools for 2026

Compare the best AI customer service software and see how Front AI helps teams deliver faster, smarter, and more human support across every channel.

Read more →Customer service

Front Unwrapped 2025: Product updates too good to re-gift

15+ new releases straight from customers’ wishlists – AI upgrades, inbox improvements, and workflows built to handle complexity and help your team deliver standout support.

Read more →Shared inbox

The 6 best customer experience software solutions for 2026

Explore the six best customer experience software platforms and their features, and discover tips for choosing the right CX tool for your business.

Read more →Help desk

7 best help desk solutions for faster, more connected support

Discover the 7 best help desk solutions for connected, human support, and learn how Front’s platform helps teams stay fast, aligned, and in control.

Read more →News

Welcoming Mike Kane, Front’s New SVP of Global Channel Sales & Partnerships

Front’s new SVP of Global Channel Sales & Partnerships, Mike Kane, shares why he joined, how he sees the TSD channel evolving, and what’s next for Front’s partner ecosystem.

Read more →Front News

- While Retail Rang Up Sales, Manufacturing Teams Quietly Became AI Power Users

- Welcoming Mike Kane, Front’s New SVP of Global Channel Sales & Partnerships

- The truth behind hitting $100M ARR: Software alone can’t build relationships. People do.

- Meet Paul Teyssier: Front’s New Chief Product & Experience Officer

- Bringing real-time customer insights to Front: Announcing our acquisition of Idiomatic

Popular

- Help AI better help your customers: 5 ways to improve your help center articles

- How to deliver above and beyond support for every customer, every time

- 5 best practices for stellar self-service support

- The secret sauce to better customer experiences? Cross-functional collaboration.

- Conquer email management: top strategies for customer service teams

Guest Writers

- Why fast, collaborative support wins customers in 2025

- 15 must-track SLA metrics to keep your team and customers aligned

- Help desk trends: how to give your service teams an edge in 2025

- How help desk workflows cut the drudge work from customer support

- Why stand-out support starts with a customer service desk